October 11th each year is World Egg Day! Billions of eggs are produced around the world each year for our own consumption, so most of us are pretty familiar with eggs. Traditionally, World Egg Day is a day to celebrate how useful eggs are to humans as a food source, but I’d like to take this opportunity to talk about the ecology of bird eggs and why I think they are a remarkable little feat of nature.

In the Spring and Summer, I volunteer for the British Trust for Ornithology – monitoring any wild bird nests I find for the Nest Record Scheme (link: Nest Record Scheme | BTO – British Trust for Ornithology). This is something I find incredibly rewarding and studying birds at the nest and working here at Wingham Wildlife Park means that I often have an incredible opportunity to observe the wonders of bird reproduction first hand.

From left to right: Reed bunting, stonechat and blackcap eggs (photographed under licence). Bird eggs come in all shapes, sizes and colours.

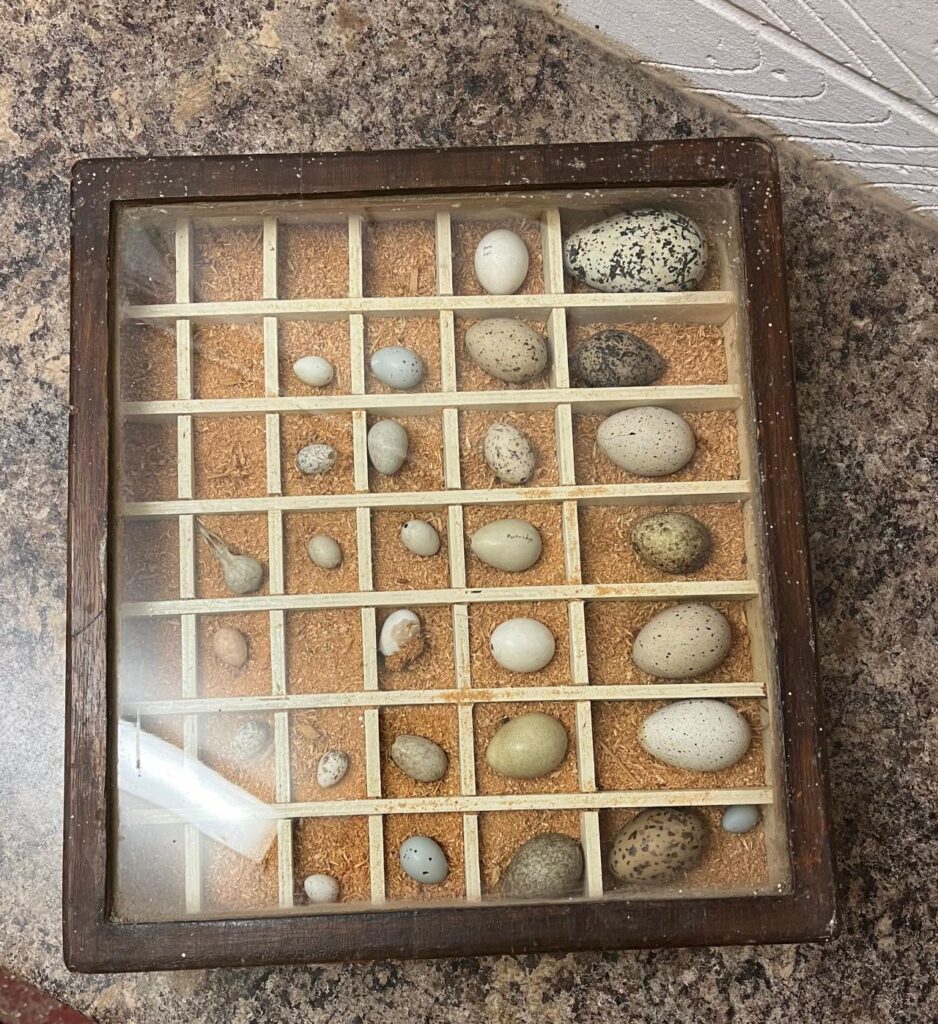

Eggs are essential to the reproduction of birds and are crucial in protecting and nourishing a bird’s chicks until they hatch. There are around 11,000 bird species described today, so naturally their eggs are similarly diverse. Eggs can vary considerably in shape, colour, patterning and size from species to species depending on how a bird has evolved and adapted to their nesting environment to suit their needs. We have always had a fascination with bird eggs, with the Victorian fanatics particularly keen on collecting them. Thankfully this is a pastime that has fallen out of favour now and it is in fact illegal in the UK nowadays to collect wild bird eggs without a licence. By the early 1900s, conservation oragnisations like the RSPB made the connection between collecting bird eggs and declining numbers of birds. These old collections and specimens from the 1800s-1900s remain an important resource for oology today (the study of eggs).

Taking wild bird eggs has been a crime since The Protection of Birds Act 1954, and in 1981 the Wildlife and Countryside Act was introduced so now it is against the law to possess the egg of any wild bird. However, if a person can show that an egg collection predates this legislation, these old collections can be useful to show how diverse bird eggs are.

From left to right: Ostrich, rhea and emu eggs. The ostrich has the largest egg of any living bird.

Because eggs are so important to us for food, we know a lot about their formation and development. When preparing to produce an egg, females need to start filling up an ova with yolk inside the ovary. On the yolk’s surface sits is a little disc called a “Germ Spot” which contains all of the genetic material needed to create an embryo. The female will need to spend this time feeding up so that she can build up a yolk that is so big that it can be transformed into a chick. Even if the female has already mated, only when she has built up enough yolk will the egg become fertilised.

I’m often asked at the park “how long are birds pregnant for?” Amazingly, minutes after fertilisation, the egg is released from the ovary and then, for most species of bird, it only takes 24 hours to journey down the oviduct and be laid. Along the way, the yolk envelops in albumen (the egg white) which contains all the water that will be needed by the growing chick. That done, it will travel into the uterus where the eggshell will form. The shell is separated from the rest of the egg by a bag called a membrane. At this stage the egg is almost complete. Lastly, calcium carbonate is deposited onto the egg’s soft membrane where it will then harden. The egg slowly rotates as it continues to pass through the uterus, and in some species, cells then release pigment which spray out spots and streaks onto the shell. The eggshell itself is also complex with pores embedded though the shell which allow the exchange of gases whilst keeping water inside.

Budgerigar eggs: Like most cavity nesting birds, budgies don’t waste energy on adding pigment to their eggs as they are safely out of sight in a hole.

Razorbill egg: Many shorebirds nest precariously on cliff faces. This razorbill egg’s pointed shape rolls in a tight circle when disturbed (photographed under licence).

Ringed plover eggs: This wading bird nests on the ground. The patterning on the eggs help camouflage the eggs and they are shaped to fit together in the nest for efficient incubation (photographed under licence).

Birds that lay multiple eggs usually lay one egg a day, but this can also vary from species to species. Unlike mammals which have a gestation period, the embryo inside the egg will need to be kept warm to develop. Some species do not start incubating their eggs straight away but wait until all of the eggs have been laid so they can start incubating them together so that they will then hatch together. This allows the parent bird to care for the chicks as a group when they are all at their most vulnerable. Some species incubate their eggs straight away, meaning that the chicks will hatch at different times. This means that the older chicks will be bigger and stronger until they all reach their full size.

Great tit chicks all hatch at the same time because the adult does not start the incubation until all of her eggs are laid (photographed under licence).

Many birds develop a “brood patch” where the feathers can be shed from their abdomen to expose wrinkled, bare skin. The parent bird can then sit on the eggs to keep them warm, keeping the egg in close contact with the skin. Some birds, like pelicans, don’t develop brood patches but use their large, webbed feet to keep their eggs warm instead! And some of the Megapodes even bury their eggs in a mound. Astonishingly the parent bird can open and close vents in the surface sand layer to keep the eggs at a constant temperature while they are heated by the compost below.

Both male and female Humboldt penguins take it in turns incubating their eggs. This means that both sexes develop a “brood patch,” a bare patch of skin to keep the eggs warm.

Pelicans incubate their eggs using their feet. By pumping more hot blood into the feet, this is also an effective way to keep eggs warm.

This incubation period is different for each species. Some birds invest some time building up large yolks, their chicks will emerge fully feathered and ready to search for food (precocial chicks). Others don’t devote resources to this, but instead spend their energy feeding naked and defenseless chicks (altricial chicks). When it comes nearer to breaking free of the egg, the eggshell that has been so strong to protect the chick undergoes some changes. The shell becomes thinner because the chick inside will absorb calcium from the shell into it’s own bones. This makes the shell weaker so that the chick can start to break free. The chick will also use the shell’s calcium to grow a tool to help it breach through the shell called an “egg tooth” which is a hard jagged tip on the end of the chick’s beak. The chick cannot break through the shell without this, but even so, it takes hours, or sometimes even days for the chick to hammer it’s way out of the shell.

Hatching Humboldt penguin: Note the egg tooth at the end of the bill. For more cute baby penguin pictures, see my previous blog here (link: Humboldt Penguins: from egg to fledgling – Animal Experiences At Wingham Wildlife Park In Kent).

One day old Vietnamese pheasant chicks can follow their parents soon after hatching.

This really is the end of the egg’s function. It’s incredible really to realise how complex the humble egg is, with each element playing its part to create the most perfect life support system for a growing baby bird. Overall we still have much to learn about the ecology of eggs, but I hope you enjoyed my crash course in egg formation and development.